Investors have been snapping up the debt of some of the eurozone’s most indebted countries to lock in attractive yields, as the traditional dividing lines between the bloc’s riskier and safer bond markets become increasingly blurred.

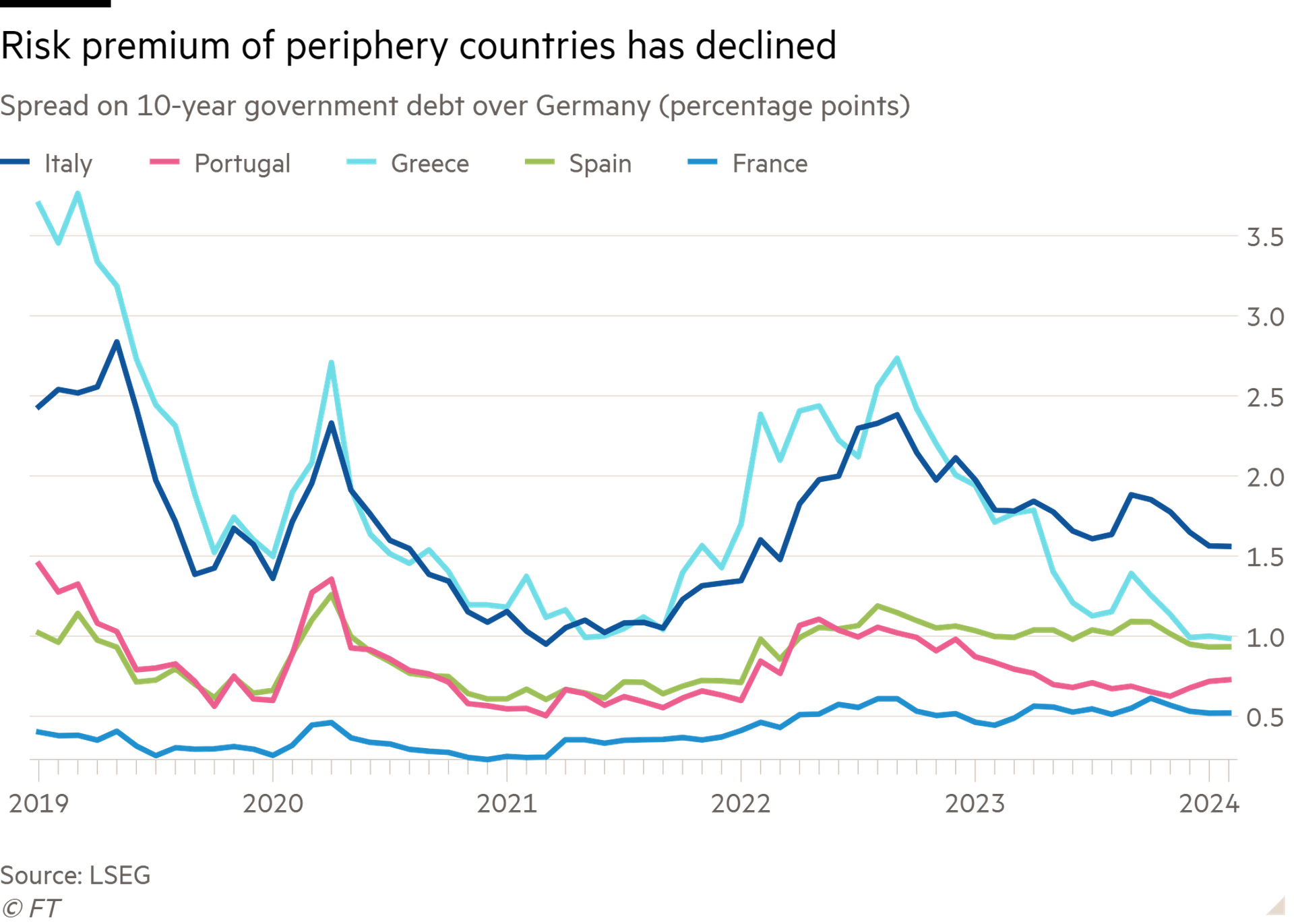

Traders have been encouraged by declining debt ratios in Italy, Portugal, Greece and Spain, say analysts. That has come on top of a broad rally in eurozone debt late last year on hopes of interest rate cuts, and helped narrow the gap between Italian and German borrowing costs — a key measure of eurozone risks — to 1.56 percentage points, near a two-year low. In October, the gap was more than 2 percentage points.

The tightening of these spreads marks a major shift in sentiment across the euro area, just over a decade after a long-running debt crisis almost broke the single currency and led to bailout loans for a number of countries.

“We think 2024 will be the year when the boundaries blur between core and periphery,” said Aman Bansal, lead European rates strategist at Citi.

He pointed to falling debt to GDP levels among peripheral nations and higher net debt issuance in France and Germany.

Christian Kopf, head of fixed income at Union Investment, Germany’s third largest asset manager, said he had profited “handsomely” from buying the debt of Greece and Portugal, adding that their public debt ratios are falling.

“It’s really quite simple,” he said. “Bonds that yield more than German Bunds are likely to also return more — unless the issuer’s solvency deteriorates significantly, which is not the case in the euro area periphery. ”

According to IMF forecasts, debt to GDP will rise in France and Belgium over the next two years but decline significantly in Greece and Portugal, with modest declines also forecast in Italy and Spain.

Eurozone debt prices have fallen this week ahead of the European Central Bank’s rate-setting meeting on Thursday, where investors will watch for any hints as to when the central bank will start lowering rates. Markets are pricing in 1.3 percentage points of ECB cuts this year.

Still, despite the ECB’s deposit rate currently at a record high of 4 per cent, economic growth has been higher over the past year in Spain, Greece and Portugal than it has been in Germany or France, while Italy’s economy has stagnated.

“Spain and Portugal have suffered less from the impact of the Russian war against Ukraine as the Iberian peninsula was less dependent on energy imports from Russia, while the Next Generation EU common debt issuance programme has benefited smaller countries the most,” said Oliver Eichmann, head of rates fixed income at Europe, the Middle East and Africa at DWS. Next Generation EU was set up in 2020 to reconstruct the region’s pandemic-stricken economies.

“There is a high likelihood that these established instruments will be used again in the future and that works in favour of less volatile spreads,” Eichman said.

The tightening of spreads comes in spite of the ECB’s announcement it would stop buying government debt earlier than planned and a gush of bond sales this month.

Citi forecasts a record €165bn of eurozone government debt will be issued this month, 13 per cent higher than January last year. But demand has remained robust as markets bet the ECB will cut rates this year, with Spain attracting the largest ever order book for a sovereign bond on January 10 while Italy received €91bn in bids for a 30-year debt sale, the largest Italian order book since the start of 2021.

Citi’s Bansal said that pressures from net issuance — after excluding bond redemptions and the ECB’s purchases — are greatest in the eurozone’s core countries, with France on track to issue a record €140bn net this year.

“France is slowly moving from a core to a periphery economy in terms of fiscal vulnerabilities,” said Tomasz Wieladek, chief European economist at T Rowe Price.

France’s annual budget deficit was 4.8 per cent of GDP in the third quarter of last year, up from 4.4 per cent the previous quarter, according to data from Eurostat this week, while Portugal, Greece and Ireland each clocked a surplus.

Meanwhile, many investors believe that the ECB’s so-far untested transmission protection instrument, which allows the ECB to buy unlimited amounts of bonds of any member country judged to be suffering from an unjustified rise in its borrowing costs, offers protection against high interest rates for the bonds of “peripheral” countries.

Mary-Therese Barton, chief investment officer for fixed income at Pictet Asset Management, said she expected a continued convergence of eurozone borrowing costs this year owing to the “collectivity of risk” across the bloc, alongside growing pressure for the eurozone’s largest countries to boost spending on defence and the energy transition.

“Despite all the doom mongers on the European project there is just this border narrative about socialisation of the debt more broadly . . . in which case spread convergence makes every sense,” Barton said.

Additional reporting by Martin Arnold in Frankfurt